Released at the start of what is being heralded as a “decade of action” for education, as the world grapples with the COVID-19 crisis, the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report illuminates how countries are putting diversity at the core of their education systems, with varying degrees of success.

“It has never been more crucial to make education a universal right, and a reality for all”, UNESCO chief Audrey Azoulay said in the report’s foreword.

Challenges abound

However, as underlying inequalities exacerbate learners’ needs, well-meaning laws and policies often falter, and educational opportunities continue to be unequally distributed, keeping quality education out of reach for many.

Even before the pandemic, one-in-five children, adolescents and youth were entirely excluded from education.

Stigma, stereotypes and discrimination mean millions more are further alienated inside classrooms, with the current crisis further perpetuating different forms of exclusion.

And while the world is “in the throes of the most unprecedented disruption in the history of education”, Ms. Azoulay stated that social and digital divides “have put the most disadvantaged at risk of learning losses and dropping out”.

“More than ever, we have a collective responsibility to support the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, helping to reduce long-lasting societal breaches that threaten our shared humanity”, she said.

Inclusivity is key

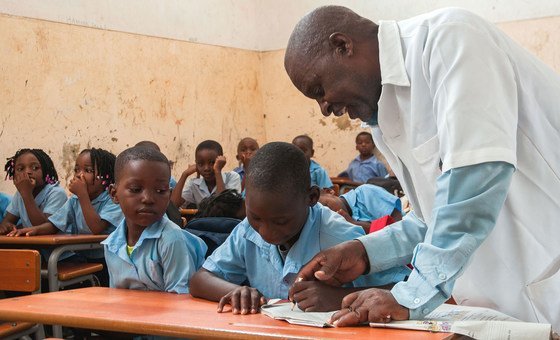

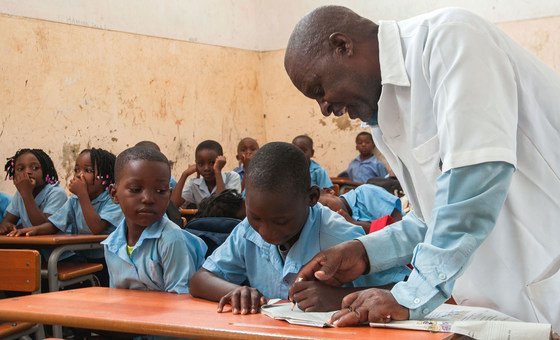

The core recommendation of the GEM report is to understand that inclusive education means equal access for all learners, notwithstanding identity, background or ability.

And it identifies different forms of exclusion, how they are caused and what can be done to mitigate them.

Moreover, GEM provides policy recommendations to make learner diversity a strength, to be celebrated as a force for social cohesion.

Ms. Azoulay noted that “the COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed and deepened” inequalities and the “fragility of our societies”.

At the same time, past lessons have shown that health crises can leave many behind, particularly poor girls who may never return to school.

As the world seeks to rebuild inclusive education systems, the report recommends practices on governance, curricula, teacher education, school infrastructure – and relations with students, parents and communities – aimed at increasing access to the classroom.

The UNESCO chief called it “a call to action we should heed”, paving the way for more resilient and equal societies in the future.

“Only by learning from this report can we understand the path we must take in the future”, she said.

A look at the numbers

Inclusion is not just an economic but also a moral imperative.

And yet, 40 per cent of the poorest countries have not supported at-risk learners during the COVID-19 crisis.

Furthermore, the law in a quarter of the world’s countries, require children with disabilities to be educated in separate settings, while only 10 per cent have laws to ensure full education inclusion.

“To rise to the challenges of our time, a move towards more inclusive education is non-negotiable – failure to act is not an option”, she concluded.