In the first of a series of features exploring the fight against trafficking in the Sahel, UN News takes a closer look at what’s behind the growth of the phenomenon.

A tangled trafficking web has been woven across the Sahel, which spans almost 6,000 kilometres from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, and is home to more than 300 million people, in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, The Gambia, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal.

The Sahel is described by the UN as a region in crisis: those living there are prey to chronic insecurity, climate shocks, conflict, coups, and the rise of criminal and terrorist networks. UN agencies expect that more than 37 million people will need humanitarian assistance in 2023, about 3 million more than in 2022.

Food insecurity is affecting millions of people in Burkina Faso.

Unravelling security

Security has long been an issue in the region, but the situation markedly degraded in 2011, following the NATO-led military intervention in Libya, which led to the ongoing destabilization of the country.

The ensuing chaos, and porous borders stymied efforts to stem illicit flows, and traffickers transporting looted Libyan firearms rode into the Sahel on the coattails of insurgency and the spread of terrorism.

Armed groups now control swathes of Libya, which has become a trafficking hub. The terrorist threat has worsened, with the notorious Islamic State (ISIL) group entering the region in 2015, according to the UN Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee’s Executive Directorate (CTED).

The G5 Sahel Force headquarters was destroyed by a terrorist attack in 2018 in Mopti, Mali.

Markets across the Sahel can be found openly selling a wide range of contraband goods, from fake medicines to AK-style assault rifles. Trafficking medication is often deadly, estimated to kill 500,000 sub-Saharan Africans every year; in just one case, 70 Gambian children died in 2022 after ingesting smuggled cough syrup. Fuel is another commodity trafficked by the main players – terrorist groups, criminal networks, and local militias.

Closing corridors of crime

In order to fight trafficking and other evolving threats, a group of countries in the region – Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Chad – formed, with the support of the UN, the Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel (G5 Sahel).

Meanwhile, cross-border cooperation and crackdowns on corruption are on the rise. National authorities have seized tons of contraband, and judicial measures have dismantled networks. Partnerships, such as the newly signed Côte d’Ivoire-Nigeria agreement, are tackling the illegal drug trade.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is a leading player in efforts to bolster security by stopping trafficking attempts.

In 2020, for example, KAFO II, a UNODC-INTERPOL operation, successfully choked off a Sahel-bound terrorist supply route, with officers seizing a bounty of trafficked spoils: 50 firearms, 40,593 dynamite sticks, 6,162 ammunition rounds, 1,473 kilograms of cannabis and khat, 2,263 boxes of contraband drugs, and 60,000 litres of fuel.

Sting operations such as KAFO II provide valuable insights into trafficking’s increasingly complex and interwoven nature, demonstrating the importance of connecting the dots between crime cases involving firearms and terrorists across different countries, and taking a regional approach.

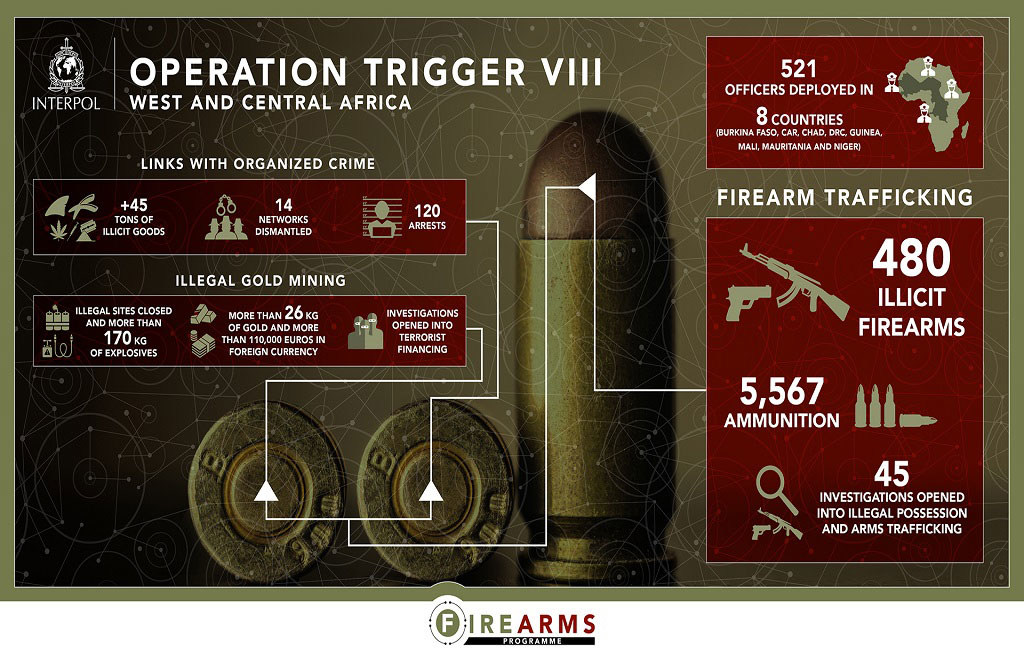

An international police operation coordinated by INTERPOL in 2022 targeting the movement of illicit firearms in Central and West Africa has led to some 120 arrests and the seizure of firearms, gold, drugs, fake medication, wildlife products, and cash.

Corruption crackdown

These insights are backed up in a raft of new UNODC reports, mapping out the actors, enablers, routes, and scope of trafficking, reveal common threads amongst the instability and chaos, and provide recommendations for action.

One of those threads is corruption, and the reports call for judicial action to be bolstered. The prison system also needs to be engaged, as detention facilities can become “a university for criminals” to broaden their networks.

“Organized crime is feeding on the vulnerabilities and also undermining stability and development in the Sahel,” says François Patuel, head of the UNODC Research and Awareness Unit. “Combining efforts and taking a regional approach will lead to success in addressing organized crime in the region.”

Crisis poses ‘global threat’

Fighting organized crime is a central pillar in the wider battle to deal with the security crisis in the region, which UN Secretary-General António Guterres poses a global threat.

“If nothing is done, the effects of terrorism, violent extremism, and organized crime will be felt far beyond the region and the African continent,” Mr. Guterres warned in 2022. “We must rethink our collective approach and show creativity, going beyond existing efforts.”

How the UN supports people of the Sahel

- The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has provided direct support to the G5 Sahel Force to operationalize and implement measures to reduce civilian harm and respond to violations.

- UNODC routinely joins national and global partners, including INTERPOL, to choke supply routes.

- The International Organization for Migration (IOM) crisis response plan aims at reaching almost 2 million affected people while addressing the structural causes of instability, with a specific focus on cross-border fragility.

- WHO launched an emergency appeal to fund health projects in the region in 2022, and works with 350 health partners in six countries.

- The UN Integrated Strategy for the Sahel (UNISS) provides direction for on-the-ground efforts in 10 countries.

- The UN Support Plan for Sahel continues to foster coherence and coordination for greater efficiency and results delivery related to the UNISS framework, in line with Security Council resolution 2391.

The UN works at building food security, which in turn, builds climate security in Mali.