Women and children increasingly bear the brunt of climate change, which deepens the inequalities and vulnerabilities they already face, such as poverty, violence, lack of opportunities and basic human rights. Yet women are not victims; they are survivors, innovators and solution-multipliers who deserve a real seat at the table. Two Colombian activists tell us why this is true.

Climate change is not gender neutral, and for activist Fatima Muriel, this fact is all too real for thousands of women in her home country, Colombia.

In 2017, disaster struck her hometown, the city of Mocoa in the department of Putumayo. Just before dawn on Saturday, April 1st, unusually heavy rains triggered flash flooding and landslides, which buried several neighborhoods along the banks of the rivers Mocoa, Sangoyaco and Mulato.

Although the region, situated in the south end of the Andes in Colombia, is notorious for frequent rains, that year, Mocoa was hit with 33 per cent of its monthly total of rainfall in one night. The ones who paid for this change in weather patterns were mainly women and children.

“Ninety per cent of all those who died were women. Since it was a Friday night, men were out drinking and partying while women were taking care of their children and parents. Among the rubble we even found some mothers holding on to two children, all drowned. It was heartbreaking,” Ms. Muriel tells UN News.

OCHA

The disaster in Mocoa in 2017 caused the death of at least 300 hundred people.

‘This is why we fight!’

Mocoa was without electricity or any type of communication for weeks. Fatima witnessed the worst of the tragedy before travelling to the capital to find help. The UN and other nonprofit organizations responded quickly in the disaster’s aftermath.

“It was extremely painful having to dig out mass graves to bury children, seeing children that were only 3-5 years old being thrown in a ditch. Some children didn’t die in the avalanche but got lost and couldn’t find their home again. Why are they the ones paying for all this?”.

Although initially deemed by authorities as a climate change-driven ‘natural disaster’, investigations are still ongoing to determine other factors that might have contributed to the tragedy that killed over 300 people and affected 45,000.

“This is why we fight. We don’t want this to happen again. Putumayo is in the middle of two great mountains. When the oil and mining companies excavate these mountains, what they do is destabilize them and that causes more landslides and the rivers to overflow”, she denounces, citing studies that indicate that deforestation in the mountains might have also played a role in the disaster.

Ms. Muriel is the President of the women’s network Tejedoras de Vida (Weavers of Life), which comprises 120 women-only organizations in the territory that seek to protect and support each other. They also openly declare their human right to a healthy environment, even as they put their lives at risk.

Alianza Tejedoras de Vida

Fatima Muriel, President of the Organization Alianza Tejedoras de Vida.

Women survivors

Unfortunately, the pain of the horror that occurred in Mocoa is only the tip in the iceberg; the women and children of Putumayo have been fighting for their survival for decades.

They have lived through the worst of times in Colombia: Putumayo was once a FARC guerilla stronghold, and the region suffered massacres and disappearances at the hands of paramilitary groups and the human right violations by some members of the security forces, as documented in reports by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Colombia (OHCHR).

Moreover, the department is fertile ground for the coca leaf, so its very soil was a victim of a massive aerial fumigation campaign launched in the 90s and early 2000s during the Government’s war against drugs. Throughout the Andes, fumigation is seen as a cause of severe economic, environmental, and health-related problems

According to Fatima, women have gotten the worst of all of it. Women have been subjected to sexual slavery, labor, forced prostitution and domestic activities, others have been raped, murdered, or disappeared.

As victims and survivors, they have assumed the family burden caused by the displacement or the hunger derived from fumigations not only eradicating coca leaf but also destroying other crops and polluting rivers.

But at the same time, women have been resilient in defense of their right to life.

Fatima Muriel herself was a victim of the war. Armed groups displaced her entire family after taking their land and kidnapping and attacking her husband leaving him disabled.

“Two of my brothers were also killed by the FARC and my brother-in-law is still disappeared. This is why I work with other women who have suffered what I suffered,” she tells UN News unable to stop the tears from rolling down her cheeks.

An education supervisor by profession, Fatima has traveled all through the region and has witnessed a systematic violation of human rights, especially to women and children, even in the most remote and isolated areas.

She has accompanied and supported teachers from rural communities who were victims of the armed conflict, confronted the former FARC guerillas to stop the forced recruitment of boys and girls for war, accompanied mothers in the search of their children and husbands who were disappeared by paramilitary groups, and witnessed the murders of women teachers and social leaders.

“On one of my trips to the municipality of San Miguel, San Carlos village, five taxis were incinerated along with their occupants, school doors were marked with different sizes of gunshots, murdered women were laying on the ground with their genitalia and breasts completely destroyed,” she recalled while speaking to a civil society group in 2020.

© UNHCR/Ruben Salgado Escudero

Women and children from the Mocoa community in Colombia light candles forming the word peace.

A network of hope

The Mujeres Tejedoras de Vida network, born as a response to the humanitarian crisis unleashed by the war in Putumayo, has been up and running since 2005.

“The most important thing in our organization is to fill women with hope, they are the ones who raise and care for the children. Wherever a woman ceases to exist, a home is destroyed, that is why we call ourselves weavers of life because we weave [together] all the projects, programmes, ideas, dreams, hopes. It is like weaving and not allowing anyone to break the fibers again as happened during the war,” says Ms. Muriel

The network is focused on three priorities: human rights and peacebuilding; public policies; and culture and the environment. They hold training sessions to help educate women about their rights and provide them with practical skills. They also offer them psychosocial, recreational, and legal support.

They have subsisted by applying for grants from international organizations, including some UN agencies and European states that help them implement specific projects to support women empowerment.

“I was working with other organizations and teachers, and at one point we counted 1,000 women killed, that’s when we realized we needed to organize ourselves and help each other,” she says, adding that they wish they had more resources to go beyond their current work, and host displaced women and children.

Fatima was part of a panel of women leaders addressing climate-related security risks during the sixty-sixth session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) held at the UN Headquarters in New York.

UNVMC

Putumayo, Colombia.

Fighting for a healthy environment

Currently, 150 women members of her organization are mapping all the rivers in their territory and the activities by mining and oil industries, as well as the State-sponsored projects that are affecting their quality of life.

“Most women in Putumayo have been displaced by the conflict. They have found a home in the riverbanks because that way they don’t have to pay for water. Water is life for them and their families, so they fight for it to be clean and not polluted by the big companies. And if you add on top of that floods caused by climate change, it means these women are being three times affected,” she explains.

Natalia Daza, who works for the Colombian NGO DeJusticia as an environmental justice researcher, tells UN News that studies show that when rivers are contaminated women are the first who notice.

“This changes the productivity in crops, leading to more food insecurity. Studies have shown that women tend to pass on their food to their children, their parents, their husbands… and they are always the last one to eat,” says the expert.

The reality is that just as it happens during wars, the burden of climate and environmental impacts falls predominantly on women and children.

The reason is vulnerability: over 70 per cent of the world’s poorest people are women. Women have less access to basic human rights, such as freedom of movement, or the ability to acquire land. Yet, they make up to 70 per cent of the agricultural workforce in some countries.

This means that when disasters strike or their subsistence crops fail, they don’t have the means to cope. Moreover, they also face systematic violence, which escalates during periods of instability. This includes child marriage, sex trafficking and domestic violence.

Research carried out in China by UN Women, for example, also showed that beyond a lack of access to resources and protection, a majority of that country’s women – as much as 80 per cent – were unfamiliar with disaster emergency plans. This makes them more vulnerable to extreme weather events, like the one that struck Mocoa.

Meanwhile, UN Environment also found that 80 per cent of people displaced by climate change are women, and they also have an increased risk of homelessness, sexual violence and disease.

According to the agency, there is also an emerging global consensus that climate change will stress the economic, social, and political systems that underpin each nation state. Climate change is the ultimate “threat multiplier” aggravating already fragile situations and potentially contributing to further social tensions and upheaval.

“In fact, climate change creates conditions that exacerbate the armed conflict in Colombia. It has been reported that there have been a greater number of disputes related to access to water resources in recent years, and it is known that those who are displaced by these conflicts tend to be women of African descent,” Natalia adds.

So, climate change is a cause and a consequence when we talk about conflict and its varied repercussions, and women and children are the most affected by both issues.

“When soil conditions deteriorate because of climate change, either due to changes in rainfall or increase in extreme temperatures, it results in conditions of vulnerability of the populations. And this makes young boys more prone to be recruited by armed groups due to the lack of opportunities and hunger,” Natalia explains.

Extreme weather events also affect children’s future and their education.

“When girls leave school, [there’s a high probability they won’t] come back. And this happens when disasters occur and essential services such as health and education are not restored quickly. The most affected are always women,” she adds.

UNVMC/Laura Santamaría

Women and children face the worst consequences of conflict and climate change.

A tough environment

But in Putumayo, the risks that women social leaders and environmental defenders face is even greater.

“Women environmentalists are the most at risk. They are committed to the territory, a territory that is in dispute by many armed actors. They are the most disadvantaged and in danger,” Fatima Muriel warns.

She describes how many women in Tejedoras de Vida have received threats for demanding their right to a healthy environment, and how some have even been killed.

“We have had to go pick up their bodies when they kill them. We have had to see children being left alone. It is so painful,” she says.

Fatima adds that unfortunately, war has returned to their territory, with several groups of FARC dissidents and other armed actors forcing women to cultivate coca leaf and sell it for whatever price they want, threatening their lives if they refuse.

“When the peace agreement was signed, we thought the war was over. We were carrying out so many projects for the 3,000 women we help, which are all victims of violence. But war has intensified again, with armed groups taking over the same territories where the FARC were before”

According to the latest report of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Colombia, at least 100 human rights defenders, including environmental defenders, were killed in 2021.

UNVMC

FARC in Putumayo gave up their arms in 2017 as part of the Colombian Peace Agreement. Here the UN is transporting them in a container.

Security actors and the environment

Fatima says a security policy is needed to protect women environmentalists, even from legal actors.

“They are exposed. The big companies have militarized their territory and when they try to intervene and stop the pollution of rivers and mercury, they are exposed to attacks or to be judicialized as criminals,” she laments, adding that any project should come with environmental guarantees and protection for the communities.

“They come with kits, hats and backpacks for the people. But what’s the use of that today, when tomorrow you’re not going to have water to live?”

Natalia Daza, who also participated of the CSW panel supported by the UN Office of Peacekeeping Operations, explains that extractive industries, and even some renewal energy ones, often come along with state and non-state security actors.

“In many cases, these actors are there to protect the mine or project, but also to discourage opposition to this type of project, which ultimately ends up threatening social leaders, especially women environmental defenders,” she explains.

Natalia argues that security actors, if involved in climate policy, should depart from a ‘human security idea’ when they act, taking in account environmental considerations.

Another issue she points out is that currently, in Colombia there aren’t specific laws on community participation in environmental lawmaking.

“There aren’t mechanisms to actually secure that communities are able to decide whether they want extractive activities on their territories. And the information that is available to them to go against the projects is really hard to read. In other countries, there are resources for people to carry out counter studies about the site where, for example, a mine is going to be set up, but in Colombia that doesn’t exist, so people are trying to do whatever they can. And when they try to go to a public audience they get threatened,” she denounces.

The 2020 OHCHR report on human rights noted Mercury contamination in several rivers in Colombia, which particularly affected indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombians and rural communities.

It also expressed concern on the negative consequences of anti-narcotic measures such as the effect of aerial fumigation on food security, adverse health impacts and denial of livelihoods.

More recently, the Office has also documented cases of State-controlled projects and private mining companies that have impacted negatively the right of rural populations to a safe, clean and healthy environment.

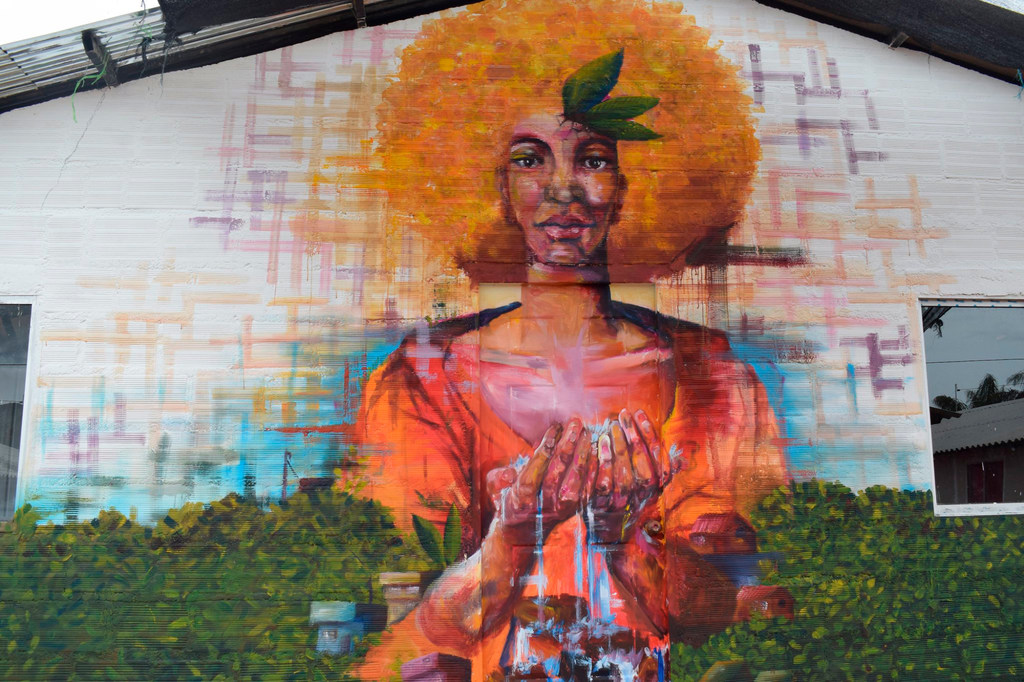

UNVMC/Laura Santamaría

A mural in a rural area in Colombia shows the relationship between women and the environment.

The ‘ethic of care’ as a solution: more women involved in climate policy

Fatima Muriel and Natalia Daza are both from Colombia, but they come from very different backgrounds, cities, and experiences. However, they agree strongly on what the solution is to protect the environment and make their country more peaceful and resilient: women participation.

“Women have to be involved in disaster prevention, they have to be involved in climate change adaptation, in education, in health, because we are 50 per cent of the population,” Fatima urges.

Natalia says it is all about the ‘ethic of care’, a normative ethical theory developed by feminists in the second half of the 20th century.

“An ethic of care shows us that there are better ways for us to relate with nature, with others, and to build a planet that will be healthy and available for all of us including the young ones”.

She argues that acting with this moral framework as a departure point would mean that communities are alerted of disasters of time, for example.

“Caring for others is making sure they have the information to make decisions in a timely manner. It would also mean that resources would be better distributed”

She puts as an example Hurricane Iota which decimated the Colombian island of Providencia in 2020.

“There had been studies about how Providencia was highly vulnerable to climate change, yet resilience strategies had not been completely implemented, and that’s leaving people without care, that’s leaving them alone. If people are being left behind there is no care for them. From a feminist perspective of care that would’ve never happened,” Natalia explains.

She adds: “Caring for them would be making sure they have the resources to build up resilience, making sure they have the information to know to have the options and the support afterward, it has been almost years since the hurricane and all services haven’t been restored including health and education.”

Women like Fatima, Natalia and the 3,000 members in Tejedoras de Vida network are an example of what it means to be a ‘solutions multiplier’ in the combat against climate change, which is a known ‘threat multiplier’.

“We are not enemies of men but of the patriarchal system. The system that has done us so much harm. That is what we have to fight for, to ensure that programmes, governments and institutions work with women. As long as we do not participate, there will be no peace,” Fatima stresses.