Born into peace but maimed by a weapon of war

Two deminers work to decontaminate the land in Bunia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“Minga had never owned a toy. In her village, in Angola, children often made do with sticks or broken wheels – but this was something different. It was green, metal and shaped like a small tin. She wanted to show her brothers and sisters, so she picked it up to take home.”

Documentary photographer, landmine survivor and UN Global Advocate for persons with disabilities in conflict and peacebuilding situations, Giles Duley, has many heartbreaking stories to tell, mostly about children maimed by landmines on their way to school, home or at play.

Six-year-old Minga lost her sight and her left arm in 2009, seven years after the end of the war in Angola. She was one of the many children who was born into peace but harmed by a war that she never knew.

Daily danger of death

More landmines have been laid in Syria due to the ongoing conflict there.

The latest estimates show that in 2021, more than 5,500 people were killed or maimed by landmines, most of them were civilians, half of whom were children. More than two decades after the adoption of the Mine Ban Treaty, about sixty million people in nearly 70 countries and territories still live with the risk of landmines on a daily basis.

The UN Mine Action Service, launched the campaign “Mine Action Cannot Wait ” to mark the International Day, as countries like Angola, Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Viet Nam, continue to suffer from decades of landmine contamination.

Landmines can lie dormant for years or even decades until they are triggered.

“Even after the fighting stops, conflicts often leave behind a terrifying legacy: landmines and explosive ordnance that litter communities,” says UN Secretary-General António Guterres in his message for the International Day.

“Peace brings no assurance of safety when roads and fields are mined, when unexploded ordnance threatens the return of displaced populations, and when children find and play with shiny objects that explode.”

Landmines, which can be produced for as little as $1, do not distinguish between combatants and civilians. Their use violates international human rights and humanitarian laws.

They not only cost lives and limbs, but also prevent communities from accessing land that could be used for farming or building hospitals and schools as well as essential services such as food, water, health care and humanitarian aid.

Landmines in Ukraine

A deminer for the State Emergency Service of Ukraine sweeps the ground for unexploded ordnance and landmines.

Despite international efforts to prevent the use of landmines they continue to be laid in conflict situations including in Ukraine following Russia’s invasion in February 2022. UNICEF and the State Emergency Service of Ukraine recently warned that around 30 per cent of the country may potentially be mined as a result of the hostilities.

In Myanmar, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, a UN-supported civil society group which reports on landmine use has observed “new and greatly expanded” use of mines by government forces. Militia groups in countries like the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo also use landmines to attack and frighten people, keeping them off their lands and away from their homes.

Butterfly wings which attract curious children

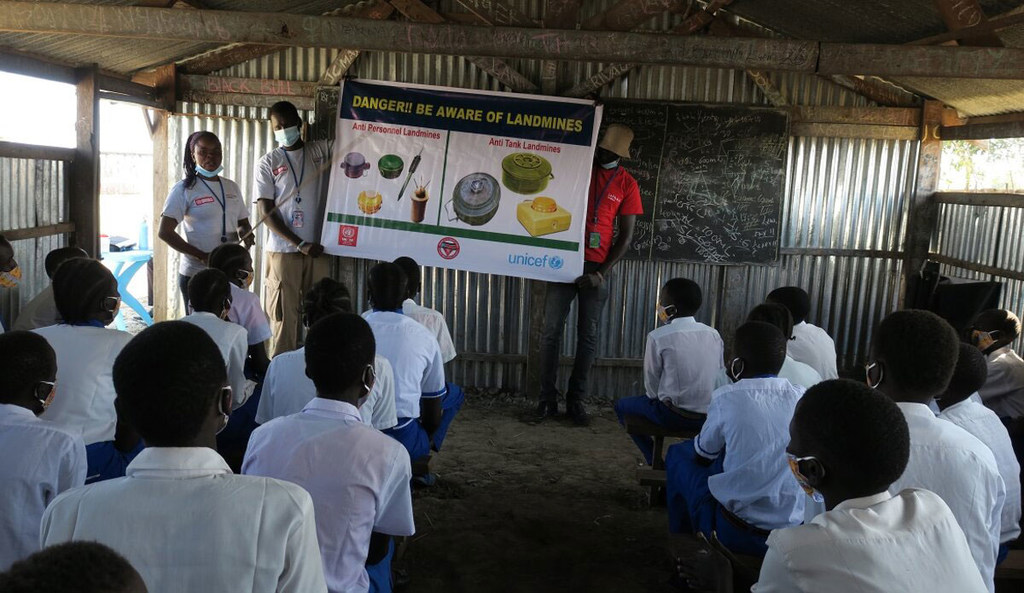

UNMAS experts teach children in South Sudan about the risks of unexploded ordnance.

There are more than 600 different types of landmines grouped into two broad categories – anti-personnel (AP) and anti-tank landmines. AP mines come in different shapes and can be found buried or above ground. A common type, known as the “butterfly” mine – comes in bright colours, making it attractive to curious children.

Landmines are also a major problem in many countries that rely on agriculture. In Viet Nam’s Binh Dinh province, where many people live off rice farming, 40 per cent of the land remained contaminated by landmines more than four decades after the war ended.

In Afghanistan, where landmines have maimed or killed more people than anywhere else, more than 18 million landmines have been cleared since 1989, freeing over 3,011 km2 of land that has benefited more than 3,000 mostly rural communities across the country.

Promise of a mine-free world

In Kandahar province, Afghanistan, deminers can find decades-old ordnance.

UNMAS and its partners have made progress on various aspects of achieving a mine-free world, including clearance, educating people, especially children, about the risks of mines, victim assistance advocacy and the destruction of stockpiles.

Since the late 90s, more than 55 million landmines have been destroyed, over 30 countries have become mine-free, casualties have been dramatically reduced and mechanisms, including the UN Voluntary Trust Fund for Assistance in Mine Action, have been established to support victims and communities in need.

Today, 164 countries are parties to the Mine Ban Treaty which is considered one of the most ratified disarmament conventions to date. However, despite the progress, broader global efforts are needed to safeguard people from landmines, according to the UN Secretary-General.

“Let’s take action to end the threat of these devices of death, support communities as they heal, and help people return and rebuild their lives in safety and security.”

Learn more about the work of UNMAS here.