As of last Friday, more than 95,000 people have been officially registered as disappeared in Mexico. That includes a worrying increase in the number of women and children, a trend that has worsened during the pandemic, with migrants particularly at risk.

Those are some of the key findings shared by the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances, at the end of a visit between 15 and 26 November, noting that more than 100 disappearances allegedly took place just during the course of their fact-finding mission.

In a statement, the Committee urged Mexican authorities to quickly locate those who have gone missing, identify the deceased and take prompt action to investigate all cases.

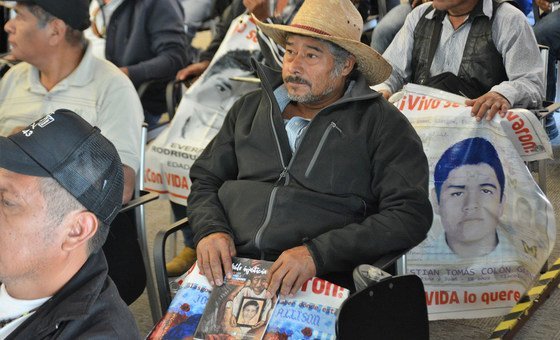

Family members of the young disappeared in Ayotzinapa., by UNIC Mexico/Antonio Nieto

Open access

The delegation went to 13 Mexican states and held 48 meetings with more than 80 different authorities. Members also met hundreds of victims, and dozens of victims’ collectives and civil society organisations, from almost every part of the country.

They witnessed exhumations and search expeditions in the states of Morelos, Coahuila and the state of Mexico, visited the Human Identification Centre in Coahuila, and went to several federal, state and migrant detention centres.

This was their first visit to the country, granted under article 33 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons against Enforced Disappearance.

For the Committee, Mexico’s acceptance of the visit is a clear expression of the State’s openness to international scrutiny and support.

“We acknowledge that some legal and institutional progress has been made in recent years, but enforced disappearances are still widespread and impunity is almost absolute”, the experts said in a statement.

With more than 52,000 unidentified bodies of deceased people, the Committee argues that “the fight against impunity cannot wait.”

Organised crime ‘collusion’

During the visit, they received “worrying information”, both from authorities and victims, about varying patterns in the way enforced disappearances are investigated in different regions.

They also point to “scenarios of collusion between State agents and organised crime”, with some enforced disappearances “committed directly by State agents.”

The Committee also notes with concern that several of the recommendations made in 2015 and 2018, are still pending implementation.

A protest rally in Mexico City on the case of Ayoitzinapa rural school attended by the 43 disappeared students.., by UNIC/Mexico

“In this sense, we stress that disappearances are not only a phenomenon of the past, but still persist”, they say.

Impunity and inaction

During these two weeks, the Committee heard victims describe a society overwhelmed by the phenomenon of disappearances, as well as systemic impunity, and their powerlessness in the face of the inaction by some authorities.

“They pointed out that day by day, in their search for answers and justice, they suffer [from] indifference and lack of progress. They have vehemently expressed to us their pain and that disappeared persons are not numbers, but human beings”, the Committee recalled.

The experts believe that the root causes of the problem have not been addressed and that the adopted security approach is “not only insufficient, but also inadequate.”

The Committee is made up of 10 independent experts, appointed by the States Parties to the Convention. Four members took part in the visit.

A final report will be discussed and adopted by the plenary of the Committee during its 22nd session, which will take place in Geneva between 28 March and 8 April 2022.