The 15-member Council is charged with taking action, through resolutions and decisions, on any threats to international peace and security, but sometimes adopting a draft into a legally binding document for the UN’s 193 Member States faces multiple hurdles.

Since the start of the Gaza war in October 2023, for example, Council members have drafted, negotiated and adopted several related resolutions while several other drafts and amendments were rejected for not having the required nine votes or being vetoed, a privilege enjoyed by its five permanent members – China, France, Russia, United Kingdom and the United States. Vetoes were indeed wielded.

Occasionally, single words, verbs or adjectives can stall the process as nations jockey for their position to prevail. In the case of some Gaza proposals, some wanted a ceasefire, others wanted a cessation of hostilities.

Sometimes the Council can’t agree. Whenever a veto is cast by a permanent Council member, a new mechanism introduced by Liechtenstein in 2022 automatically triggers the President of the General Assembly to convene a formal meeting of UN Member States or an emergency special session to discuss the disputed issue.

Another route came with the Uniting for Peace resolution, adopted in 1950, which basically sets out that if the Security Council fails to exercise its responsibility to maintain international peace and security, the General Assembly may call an emergency special session.

To date, 11 emergency special sessions have been convened. The Uniting for Peace resolution was implemented 13 times between 1951 and 2022, invoked by both the Security Council (eight times) and the General Assembly (five times). Eleven of those cases took the form of emergency special sessions.

However, the process of drafting resolutions remains largely unchanged since the Council adopted its first resolution in 1946 to establish a UN military staff committee. From an idea to a legally binding document for all 193 UN Member States, we followed the journey of a draft resolution.

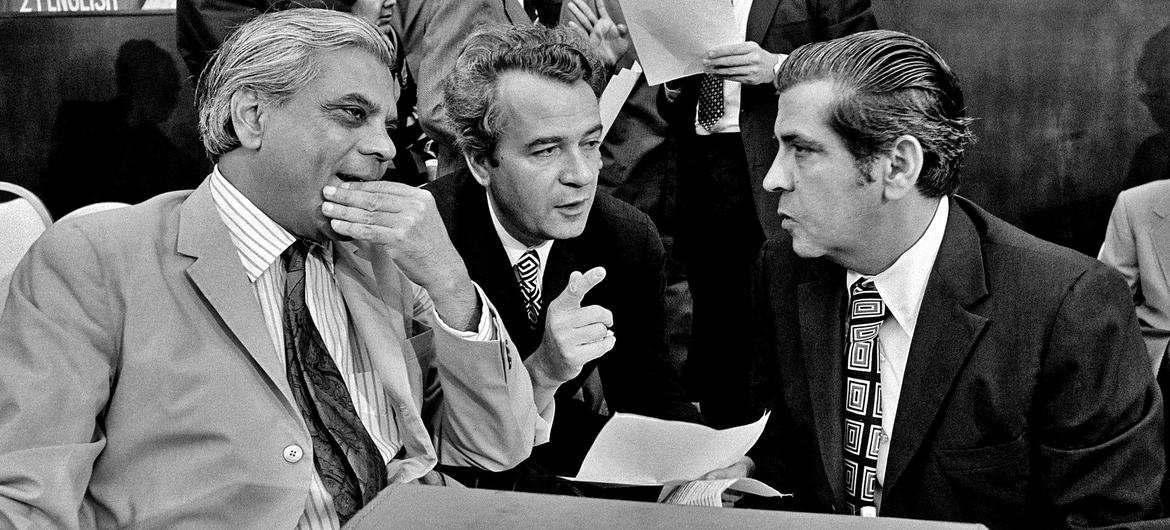

Security Council members from (beginning second from left) India, Egypt and Nicaragua confer informally on a draft resolution before the start of a meeting in New York in 1984. (file)

Getting started

The first step is producing an initial draft, which can be sponsored by one or more Council members.

Producing an initial draft on such a crisis as Gaza can be extensive and expand far beyond the 15 members, according to Nikolai Galkin, a senior political affairs officer with the UN Secretariat’s Security Council Affairs Division.

The process typically begins with counsellors from the member’s permanent mission to the UN in New York that specialise in the matter at hand. These experts may hold consultations with regional groups, the country of concern and other key stakeholders as well as counterparts in Council member delegations.

The goal is to unanimously or by a majority adopt a resolution calling for action to end a conflict, approve a peacekeeping mission, impose sanctions or refer a case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), all part of the Council’s mandate according to the UN Charter.

At this stage, the draft’s sponsor, or penholder, will often try to include as many voices as possible with this in mind.

Council members from Pakistan, then-Yugoslavia and Panama discuss a draft resolution on Latin America before a meeting in Panama in 1973. (file)

A ‘zero draft’

Next, the initial idea is revised into a “zero draft”.

That means it is “not even a proper draft per se”, Mr. Galkin said.

Rather, it is a literal draft text produced for Council members’ comments, which its penholder, would have its experts include in a further revised version.

Once the zero draft is ready, it is circulated, most often by email. The penholder then requests further input from Council members, collecting them by email, in person or casually via WhatsApp.

Before a Security Council meeting begins in Panama in 1973, members hold discussions after receiving a second draft resolution on Latin America. (file)

Negotiations and compromise

Disagreements exist. For the Gaza zero draft penned by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in December, there was much disagreement over the term “ceasefire”, which played out in news coverage of the process.

Some delegations had said they would support (or not support) the inclusion of that term.

In general, negotiations ensue to iron out differences. They are typically held off the premises, and only in rare occasions do members book a formal “informal” discussion in the Consultations Room, steps across the hallway from the Council Chamber.

Sometimes, comments on drafts are not even made in New York, but go back to the capitals of members’ home countries.

A view of documents outlining the agendas for three Security Council meetings. (file)

What goes ‘in blue’?

After one or more rounds of back-and-forth discussions, the penholder circulates a final draft. In the UAE’s case, the finalised Gaza draft was sent it to the wider UN membership, which sometimes occurs. Within 24 hours, 97 UN Member States had co-sponsored it.

At this point, a revised draft is given a document number, and the text is formatted and published “in blue” for email circulation to Council members.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, drafts were printed in blue ink and distributed at each Council member’s seat and at the Chamber’s documents counter. Going eco-friendly, drafts are no longer printed, but emailed to Council members, still appearing in blue.

Why blue? The decades-old reason came serendipitously from a photocopy machine in the corner of the Security Council offices. It printed small quantities of drafts for the 15 members, and the only available ink was blue.

Once “in blue”, it typically means the Council is ready to take action. That usually happens within 24 hours, when a formal meeting is called.

In 2017, before the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, delegates collected documents from a conference officer in the Security Council Chamber. (file)

Vote and veto

At a scheduled formal open meeting, members gather around the Security Council Chamber’s iconic horseshoe table. The monthly president gavels open the session and calls for a vote. Some may make statements before the vote, expressing their delegation’s positions or reservations. Some may even introduce amendments to the draft.

Then, it is time for action.

“All in favour, raise your hands,” the Council president says.

A show of hands around the table indicates in favour, against and abstentions. A least nine votes are needed for a draft to be adopted unless a veto is cast, a privilege held by the five permanent Council members – China, France, Russia, United Kingdom and the US.

The president proceeds to read out the final vote, and the draft is either adopted or rejected.

United States Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield votes in abstention of the draft resolution in the UN Security Council meeting on the situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question. (file)

From blue to black

The last step is producing and circulating the finalised document, which is translated into the UN’s six official languages – Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish – and published in black.

All drafts, rejected or adopted, are numbered and entered into the UN documents system.

For those looking for drafts from the past, Mr. Galkin said that in the coming months, new measures are in the works to make it easier to find all draft resolutions, rejected or adopted, on the UN Security Council website.

The Birth of a United Nations Document exhibit in 1948 included a display of official Security Council records. (file)