Releasing its 2023 World Malaria Report as nations gather at the UN climate change conference, COP28, the health agency warned that despite expanding access to malaria prevention, more people are getting sick with the disease.

WHO documented 249 million cases in 2022, an increase of two million from 2021 and exceeding the pre-pandemic level of 233 million in 2016.

Nexus between malaria and climate change

That’s primarily due to COVID-19-induced public health disruptions, humanitarian crises, drug and insecticide resistance, and global warming impacts.

“The changing climate poses a substantial risk to progress against malaria, particularly in vulnerable regions,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General.

“Sustainable and resilient malaria responses are needed now more than ever, coupled with urgent actions to slow the pace of global warming and reduce its effects,” he added.

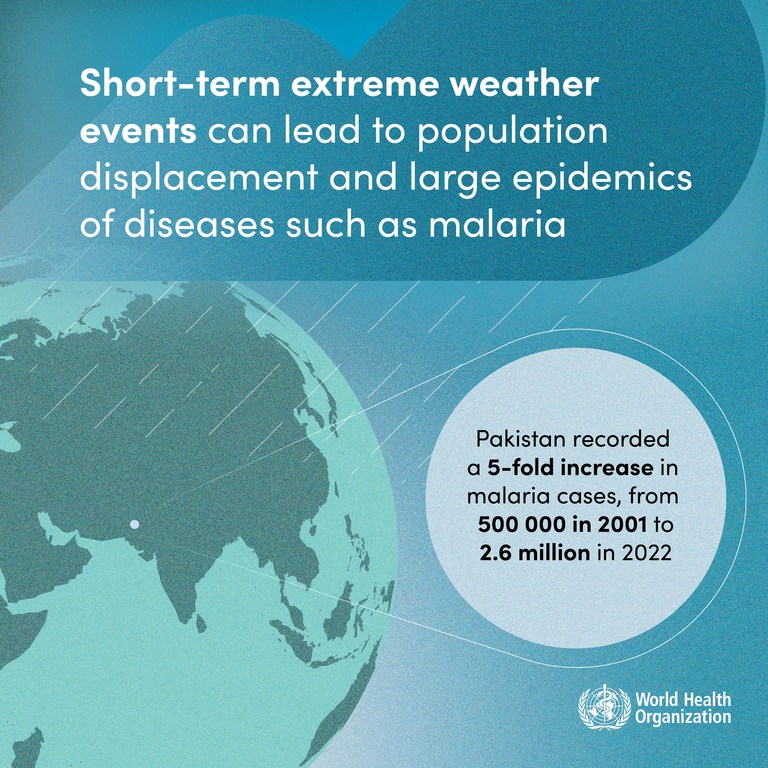

Five-fold increase in Pakistan

The report also delved into the link between climate change and malaria, noting behavioural changes and increased survival rates of the Anopheles mosquito through rising temperature, humidity and rainfall.

Extreme weather events, such as heatwaves and flooding, can also directly impact transmission and the disease burden. For instance, the catastrophic 2022 flooding in Pakistan led to a five-fold increase in malaria cases in the country, the agency said.

Significant increases were also observed in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea and Uganda.

Cascading impacts

WHO also stated that climate variability can have indirect effects on malaria trends, due to factors such as reduced access to essential malaria services and disruptions to the supply chain of insecticide-treated nets, medicines and vaccines.

Climate change-related population displacement could also lead to increased malaria cases as individuals without immunity migrate to endemic areas.

Other factors

While climate change posed a major risk, WHO also underscored the need to acknowledge a multitude of other threats.

“Climate variability poses a substantial risk, but we must also contend with challenges such as limited healthcare access, ongoing conflicts and emergencies, the lingering effects of COVID-19 on service delivery, inadequate funding and uneven implementation of our core malaria interventions,” said Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa.

“To forge ahead toward a malaria-free future, we need a concerted effort to tackle these diverse threats that fosters innovation, resource mobilization and collaborative strategies,” she added.

A health worker in Kenya holds vials of malaria vaccine to be administered at a vaccination campaign.

Grounds for optimism

The report also cited achievements such as the phased roll-out of the first WHO-recommended malaria vaccine, RTS,S/AS01, in three African countries.

A rigorous evaluation has shown a substantial reduction in severe malaria and a 13 per cent drop in early childhood deaths from all causes in the areas where the vaccine has been administered compared with areas where it has not, according to WHO.

In addition, a second safe and effective malaria vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, was approved last month, which is expected to increase supply and enable large-scale vaccine deployment across Africa, where most cases are concentrated.

Next steps

WHO highlighted the need for a “substantial pivot” in the fight against malaria, with increased resourcing, strengthened political commitment, data-driven strategies and innovation focused on the developing more efficient, effective and affordable products.

“The added threat of climate change calls for sustainable and resilient malaria responses that align with efforts to reduce the effects of climate change. Whole-of-society engagement is crucial to build integrated approaches,” it urged.