The UN biodiversity conference, COP15, is due to wrap up on 19 December. This weekend, we are looking at some of the ways that humanity is reliant on biodiversity for a healthy and thriving global ecosystem.

When a species goes extinct, it takes with it all of the physical, chemical, biological, and behavioural attributes that have been selected for that species, after having been tested and re-tested in countless evolutionary experiments over many thousands, and perhaps millions, of years of evolution.

These include designs for heating, cooling, and ventilation; for being able to move most effectively and efficiently through water or air; for producing and storing energy; for making the strongest, lightest, most biodegradable and recyclable materials; and for many, many other functions essential for life.

Nature’s value is not limited to human applications, but the loss of nature and biodiversity represents major losses to human potential as well.

Here are some examples of the ways that nature has inspired engineering solutions.

Way of the dragonfly

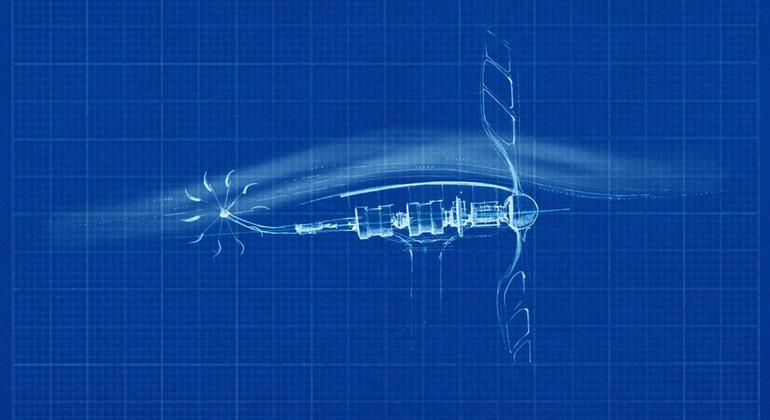

Inspired by the energy efficiency of dragonfly wings, particularly at low wind speeds, Professor Akira Obata, formerly from Japan’s Nippon Bunri University, designed corrugated blades for micro-wind turbines that turn and generate electricity, at wind speeds as low as 3 kph.

Most wind turbines perform poorly when speeds are less than 10 kph; some will not turn at all. By lowering the minimum wind speed requirements, these micro-wind turbines can harness wind energy in easily accessible locations like rooftops and balconies, and not need expensive towers to capture the higher speed winds found at higher elevations.

By studying and understanding the aerodynamics of dragonfly flight, Obata was able to make inexpensive, lightweight, stable, and efficient micro-wind turbines that can be used in off-grid locations in developing countries.

What is blacker than black?

Some butterflies, birds, and spiders have evolved super black coloration achieved by a variety of complex light-trapping mechanisms that could lead to new energy-efficient designs for solar collection.

The micro and nano-structures of surfaces strongly determine their light absorptive or reflective properties. Understanding not only the composition of the pigments involved but also the fine-structure and the physics of these surfaces, may be useful in designing more energy efficient systems for heating and cooling buildings, and more productive solar energy collectors.

‘Fog basking’

Two species of beetles actively harvest water from fog with a sequence of behaviours called ‘fog basking’. Late at night, in advance of the fog that rolls in nightly in the coastal sections of the Namib desert, the beetles emerge from the sand and climb up the dunes to place themselves in the fog’s path.

Tilting their bodies forward while facing the fog, they harvest moisture on their backs, which are made of hardened forewings called elytra that cover and protect their hind wings, used for flying.

The small water droplets in the fog collect there, coalesce to form larger droplets, which, by the force of gravity, run down the smooth hydrophobic (i.e. water-repelling) surfaces to the beetles’ mouths.

Given WHO estimates that half the world’s population will be living in water-stressed environments by 2025, the specific chemistry and structure of hydrophobic surfaces found in Namib beetles has generated enormous scientific interest for their potential human applications.

Birds and fossil fuels

Gliding and soaring birds are masters of aerodynamic efficiency and their wing-tip feather design inspired engineers to add small up-turned ‘winglets’ that reduce drag caused by vortices at the tips of aircraft wings.

By copying this wing-tip design, commercial airlines have saved 10 billion gallons of fuel, reducing their CO2 emissions by 105 million tonnes per annum.

To sequester this amount of carbon, one would need to plant about 16 million hectares of trees, each year – an area larger than the territory of Norway or Japan.

Extinction is not a foregone conclusion

The wastefulness of extinction is perhaps best highlighted by the near-extinction of the humpback whale.

Over-hunting almost wiped out these gigantic creatures, among the largest to ever have lived on the planet, and the humpback population crashed to just 5,000 in 1966.

Conservation organizations and scientists prompted a huge public and political outcry and humpback whales bounced back to an estimated 80,000 today. The humpback, uniquely, has bumpy ‘tubercles’ on the front of its flippers that enable these giants to manoeuvre with extraordinary agility.

The tubercles give the whales a hydrodynamic advantage – they minimize drag, enhance their ability to stay in motion and, critical when attacking prey, allow them to turn at sharper angles. Among other applications these have inspired engineers to make some of the most efficient industrial fan blades and wind power generators. If the humpbacks had gone extinct, we might have never been able to avail ourselves of the tubercle design.

The extraordinary organisms featured above, along with the sustainable engineering designs they have inspired, present a compelling case for why we must preserve biodiversity.

The organisms that create the support systems make all life on Earth, including human life, possible: millions of species are at risk, but losing even a single species can have enormous negative consequences for humanity.

The story is based on the UN Development Programme (UNDP) booklet, How Sustainable Engineering Solutions Depend On Biodiversity