From bringing together fractured communities, to fighting child labour, and advancing climate action, the work of UN staff around the world is contributing to progress and development in many different ways.

To mark UN Day this year, UN News is taking a snapshot of just one part of world – featuring the diverse contributions made by former staff members in Brazil.

The UN Country Team in Brazil is celebrating the occasion by highlighting the contributions of four former staffers who’ve all played a role in the Organisation’s history: a veterinarian, an environmentalist, a sociologist, and a demographer.

All of them have dedicated a large part of their lives to the UN, and believe that unity and dialogue are the best way to bring about a fairer and more sympathetic world.

UN Brazil/Isadora Ferreira

Milton Thiago de Mello at home in Brasilia.

Milton Thiago de Mello, Veterinarian

“The world after the pandemic will be different – the planet was forced to take a break, and a new world will come out of that”.

This philosophical take on COVID-19 comes from a former UN staffer who has earned the right to provide a long-term view. After all, this is the second pandemic he has lived through: now 105-year-old, Milton Thiago de Mello was a small child when Spanish flu was spreading around the world, killing tens of millions of people.

As well as surviving that global health crisis, Mr. Thiago de Mello lived through two world wars, and travelled to many cities and countries, working tirelessly in the service of scientific progress.

His research on brucellosis, an infectious disease that affects livestock and human health, brought him to the attention of the Pan American Health Organization and the World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), for whom began working in Argentina, during the year the health agency was created, in 1948.

UN Brazil

Cristina Montenegro worked at the UN, in Brazil and abroad, for thirty years.

Cristina Montenegro, environmentalist

“I paved the way for many women in the UN System”

Cristina Montenegro’s international UN career spanned three decades, and by the time she retired she was the head of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in Brazil, one of the first women in the Organisation to run an agency country office.

After working at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (better known as the 1992 Earth Summit, in Rio), the environmentalist went on to serve in Mexico, before returning to Brazil to open the first UNEP country office.

“We started in a period when little was said about the environment”, she reminisced. “Then we had a boost in 1992 with the Rio Conference, which strengthened the theme and institutions.”

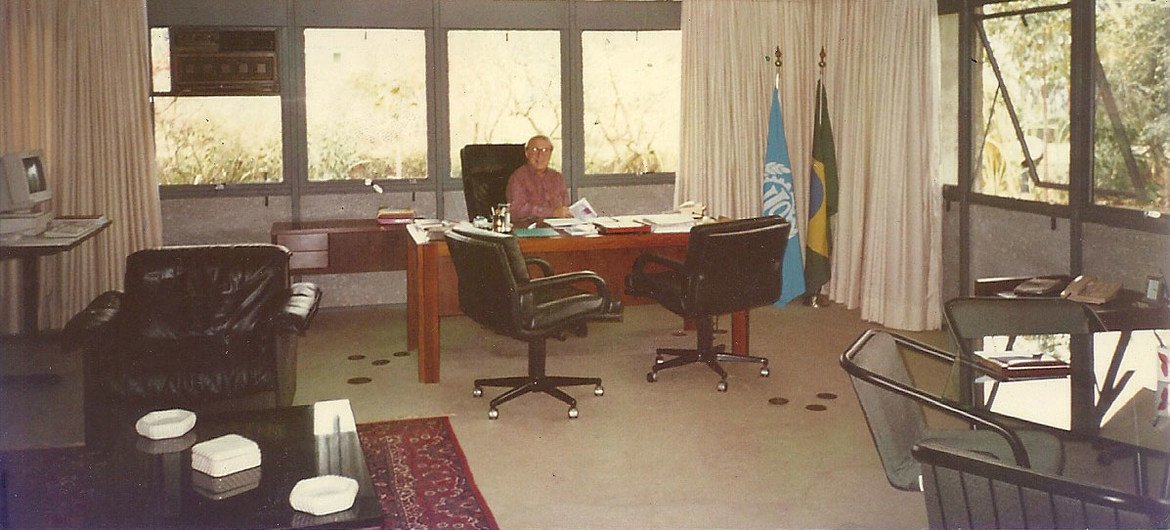

UN Brazil

João Carlos Alexim at the ILO office in Brazil.

João Carlos Alexim, sociologist

João Carlos Alexim ran the Brazil country office for another UN agency, the International Labour Organization (ILO).

During his career as a sociologist, he was involved in some pioneering projects, including initiatives that advanced the fight against child labour, and improving equal opportunities and salaries for Black and women workers.

“For me, the United Nations remains the fundamental organisation centre for human thought and civilization”, he says, emphasizing the values that founded the UN, which remain relevant today.

UN Brazil

Mena and British actress Vanessa Redgrave, who was invited to Bósnia by UNESCO to work with local artists.

Mena Mueller, demographer

Mena Mueller’s full name is Maria Helena Fernandes da Trindade Henriques Mueller, but the preference for the shorter nickname came about whilst she was working for renowned UN official, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, during his time as the head of the emergency office of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Bosnia, when he participated in negotiations to end the war in the country that killed more than 97,000 people.

Ms. Mueller was tasked with the complex mission of uniting the three conflicting groups (Bosnians, Croats, Serbs), with a shared cultural identity.

This involved mobilising artists, journalists, activists and educators, to prove to the people of the former Yugoslavia, and the outside world, that the countries and historic cultures needed to be supported.

“When we arrived in the country it was difficult to convince people that they weren’t dead. Especially young people”, she says. “It was a huge job to encourage them to go on, and to find enough hope to build meaningful lives”.