“Every time I talk about it, I cry,” she told UN News, describing how propaganda spread messages of hate that sparked a deadly wave of unspeakable violence. She lost 60 family members and friends in the mass slaughter.

Ahead of the UN General Assembly’s commemoration of the International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, Ms. Mutegwaraba spoke with UN News about hate speech in the digital age, how the 6 January attack on the United States Capitol triggered deep-seated fear, how she survived the genocide, and how she explained the events that she lived through, to her own daughter.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

UN News: In April 1994, a call was put out over the radio in Rwanda. What did it say, and how did you feel?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: It was terrifying. A lot of people think the killing started in April, but beginning in the 1990s, the Government put it out there, in the media, newspapers, and radio, encouraging and preaching anti-Tutsi propaganda.

In 1994, they were encouraging everyone to go to every home, hunt them down, kill kids, kill women. For a long time, the roots of hatred ran very deep in our society. To see the Government was behind it, there was no hope that there were going to be any survivors.

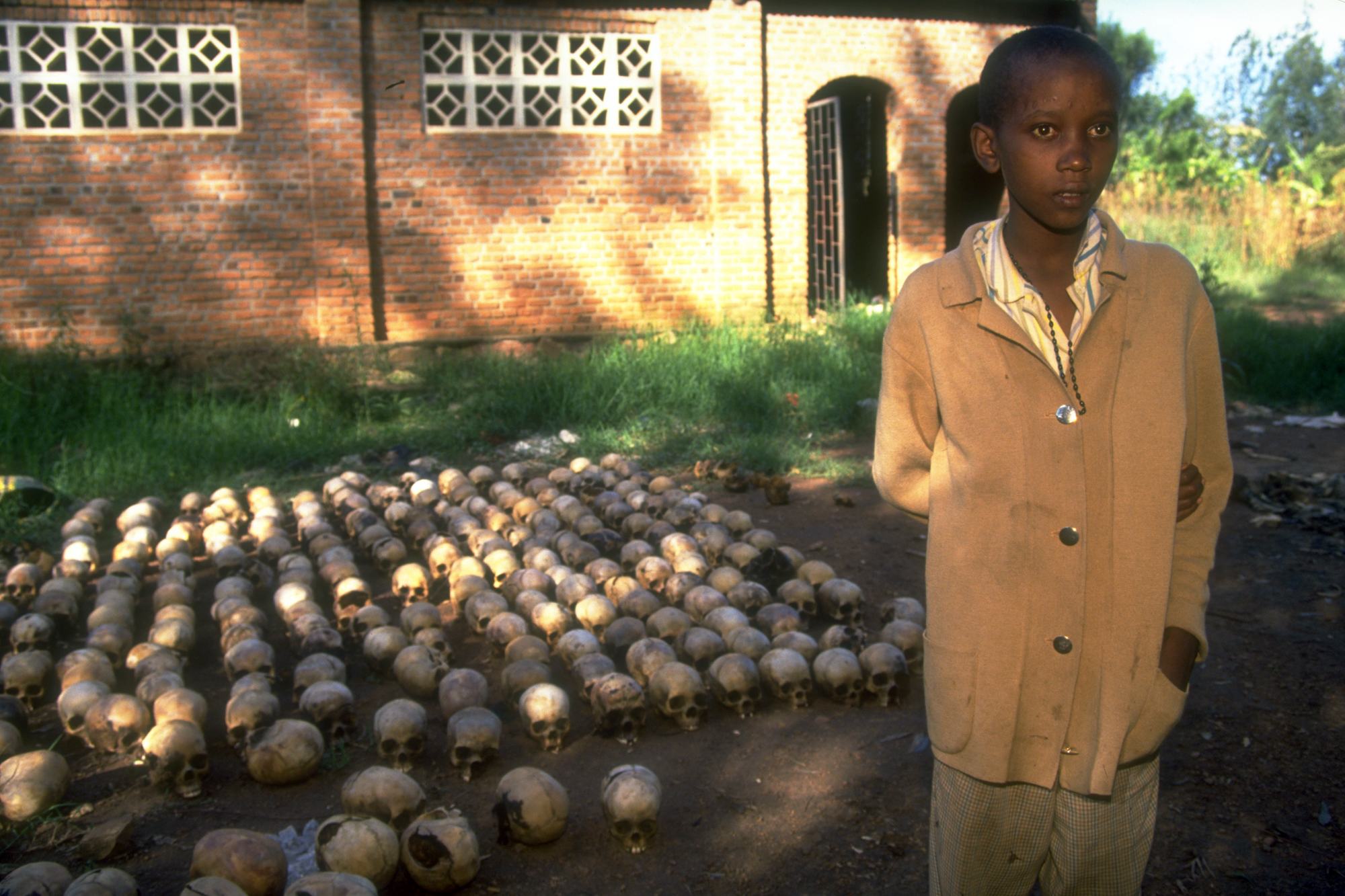

A 14-year-old Rwandan boy from the town of Nyamata, photographed in June 1994, survived the genocide by hiding under corpses for two days.

UN News: Can you describe what happened over those 100 days, where more than a million people were killed, mostly by machetes?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: It wasn’t only machetes. Any tortuous way you can think about, they used. They raped women, opened pregnant women’s wombs with a knife, and put people in septic holes alive. They killed our animals, destroyed our homes, and killed my entire family. After the genocide, I had nothing left. You could not tell if there was ever a house in my neighbourhood or any Tutsi there. They made sure there were no survivors.

UN News: How do you heal from that terror and trauma? And how do you explain what happened to your daughter?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: The genocide complicated our life in many ways. To be aware of your pain is very important, then surround yourself with people who understand and validate your story. Share your story and decide not to be a victim. Try to move forward. I had so many reasons to do that. When I survived, my young sister was only 13, and she was the main reason. I wanted to be strong for her.

For years, I didn’t want to feel my pain. I didn’t want my daughter to know because it was going to make her sad, and see her mother, who was hurt. I didn’t have answers for some questions she asked. When she asked why she doesn’t have a grandfather, I told her people like me don’t have parents. I didn’t want to give her an expectation that she was going to see me when she walks down the aisle and gets married. There was nothing to give me hope.

Now, she’s 28 years old. We talk about things. She read my book. She’s proud of what I’m doing.

UN News: In your book, By Any Means Necessary, you address the healing process and the phrase “never again”, connected to the Holocaust. You also spoke about the attack on the capitol in Washington, DC on 6 January 2021, saying you hadn’t felt that feeling of fear since 1994 in Rwanda. Can you talk about that?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: We keep saying “never again”, and it keeps happening: the Holocaust, Cambodia, South Sudan. People in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are being killed now, as I’m speaking.

Something needs to be done. Genocide is preventable. Genocide doesn’t happen overnight. It moves in degrees over years, months, and days, and those orchestrating genocide know precisely what they intend.

Right now, my adopted country, the United States, is very divided. My message is “wake up”. There’s so much propaganda happening, and people are not paying attention. Nobody is immune to what happened in Rwanda. Genocide can happen anywhere. Do we see the signs? Yes. It was shocking to see such a thing happening in the United States.

Racial or ethnic discrimination has been used to instill fear or hatred of others, often leading to conflict and war, as in the case of the Rwanda genocide in 1994.

UN News: If the digital age existed in 1994 in Rwanda, would the genocide have been worse?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: Totally. Everybody has a phone or television in a lot of developing countries. A message that used to take years to spread can now be put out there, and in one second, everybody in the world can see it.

If there was Facebook, Tik Tok, and Instagram, it would have been much worse. The bad people always go to youth, whose minds are easy to corrupt. Who is on social media now? Most of the time, young people.

During the genocide, a lot of young people joined the militia and participated, with a passion. They sang those anti-Tutsi songs, went into homes, and took what we had.

UN News: What can the UN do about quelling such hate speech and preventing a repeat of what that hate speech grew into?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: There is a way for the UN to stop atrocities. During the 1994 genocide, the whole world turned a blind eye. Nobody came to help us when my mother was being killed, when hundreds of ladies were being raped.

I hope this will never happen again to anybody in the world. I hope the UN can come up with a way to respond quickly to atrocities.

Wall of Rwanda Genocide victims’ names at the Kigali Memorial Centre

UN News: Do you have a message for young people out there maneuvering through social media, seeing images, and hearing hate speech?

Henriette Mutegwaraba: I have a message for their parents: are you teaching your kids about love and caring about their neighbours and community? That’s the foundation for raising a generation that will love, respect neighbours, and not buy into hate speech.

It starts from our families. Teach your kids love. Teach your kids to not see colour. Teach your kids to do what is right to protect the human family. That’s a message I have.